kingdom of recycling

KINGDOM OF RECYCLING

a look into the lives of China's recycling workers

Sitting on his bed, Mr Zhang stares out the window of his small bedroom in a recycling depot on the outskirts of south Beijing, China. The recycling yard he worked in shut down at the start of 2015 and he has recently found himself unemployed. At 64 years of age, Mr Zhang has seen many changes. During the 1980s he left his home in Gushi, Henan Province, and came to Beijing to look for work. “If I stayed in Henan, my only option was begging," he says. Here in the capital of China, he entered a career in recycling — collecting and sorting trash, work he found through his network of friends and family. Over the years he’s worked in many areas of the industry. He even boasts he worked for Zhongnanhai, or China’s ‘White House’. For the last few decades Henan migrants, like Mr Zhang, have moved to Beijing to both find and lose their fortunes by sorting and collecting trash.

IN BEIJING

Sorting through the empire of trash created by the millions of Beijing residents is not the most glamorous occupation, but someone has to do it. “In China the recycling industry is fuelled by the individual, the government has little influence on it,” says Chen Liwen from Nature University, an environmental organisation focusing on recycling. Working in recycling, sifting through waste, is the lowest rung of the social ladder.

"If I had stayed in Henan, my only option was begging,"

In 2010 over 10 million migrants had left Henan, making it the province that saw the largest exodus in the last decades of the China-wide trend of rural to urban migration. “Henan Ren,” or Henan people, are negatively referenced throughout China as liars, cheats and thieves. This stigma made finding reliable work and housing difficult for people from Henan, as many employers, landlords and local police treated them with mistrust. A consequence that led to Henan workers banding together and living within their recycling compounds. These enclaves are often referred to as “Henan villages” by the local Beijing residents.

Movement from rural to urban China is described as the largest migration in human history. In 2014, China Labour Bulletin estimated there were 274 million migrants — roughly the population of Indonesia, the fourth most populous country in the world. As the reforms of 1979 opened up China to the market, a steady flow of farmers travelled to find their fortunes along the rapidly industrialising eastern coast — Shanghai, Beijing and Guangdong. Migrants landed low-paid jobs in manufacturing, services and construction.

A migrant worker from Gushi sorts trash in Lang Dai, Beijing.

The household registration system (Hukou) in China ties people to services only available to them in their home province. Services such as subsidised healthcare and education. Despite this, many people made, and continue to make, the move to the larger cities for more opportunity than their own city or village can offer them.

In 2014, 62% of migrants worked without legal contracts, making them vulnerable to extortion and discrimination by employers or landlords. Older migrants, many of whom have missed out on an education, are illiterate and even more vulnerable to extortion and discrimination. Regardless, the unprecedented growth rate of the Chinese economy over the last few decades has provided many migrants with the chance to earn a higher income in the city.

At the turn of the century unprecedented economic growth fuelled by urbanisation and the demand for raw materials made recycling a gold mine. Henan migrants flocked to the industry to find recycling profitable and lucrative.

“In the best year, I could earn 200,000 RMB recycling,” reflects Mr Chen, a returned migrant in Henan. But things are changing, and fast. With economic growth predicted to remain around 5–7% for the next few years, the golden years for recycling are well over. China no longer remains the world’s factory.

““In the best year, I could earn 200,000 RMB recycling.””

Ah Hongbin's recycling yard lies empty in Lang Dai, Beijing.

Chinese economic growth is closely linked to the recycling industry. The industry prices for recyclable materials, such as metals and plastics, are pinned on global prices. Prices that can change overnight according to both global and domestic Chinese markets. After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, “recycling became a sunset industry,” says Mr Chen. That year he lost almost one million RMB. “I would buy copper for 78 RMB per tonne and couldn’t sell it for more than 18 RMB.”

The past year’s economic slump culminating in the recent Chinese market crash has hit the recycling industry hard. Ah Hongbin, another Henan migrant who still lives in Beijing, quit the business at the start of 2015. He was making no more than 30,000 a year.

““The local government only gives us a lease for one month now, before we could get a lease for ten years””

It’s not just the economic slow down the recycling industry faces in Beijing, but the local government. For the government, removal of labour intensive industries, such as recycling, is a plan of economic transition, a way to regulate recycling and move the industry outside of the capital. The demolition of recycling depots doesn’t just mean the removal of where migrants work, but also where they live.

“My family moved here just a few months ago to recycle, now the government is pushing us out again,” says Mr Chen, another migrant from Henan. Mr Chen works in Dongxiaokou, one of the largest recycling villages in Beijing. “The local government only gives us a lease for one month now, before we could get a lease for ten years.” Each year the recycling depots are being pushed further and further into the outskirts of Beijing. Mr Chen is not sure what his next steps are and is considering returning home to farm his land.

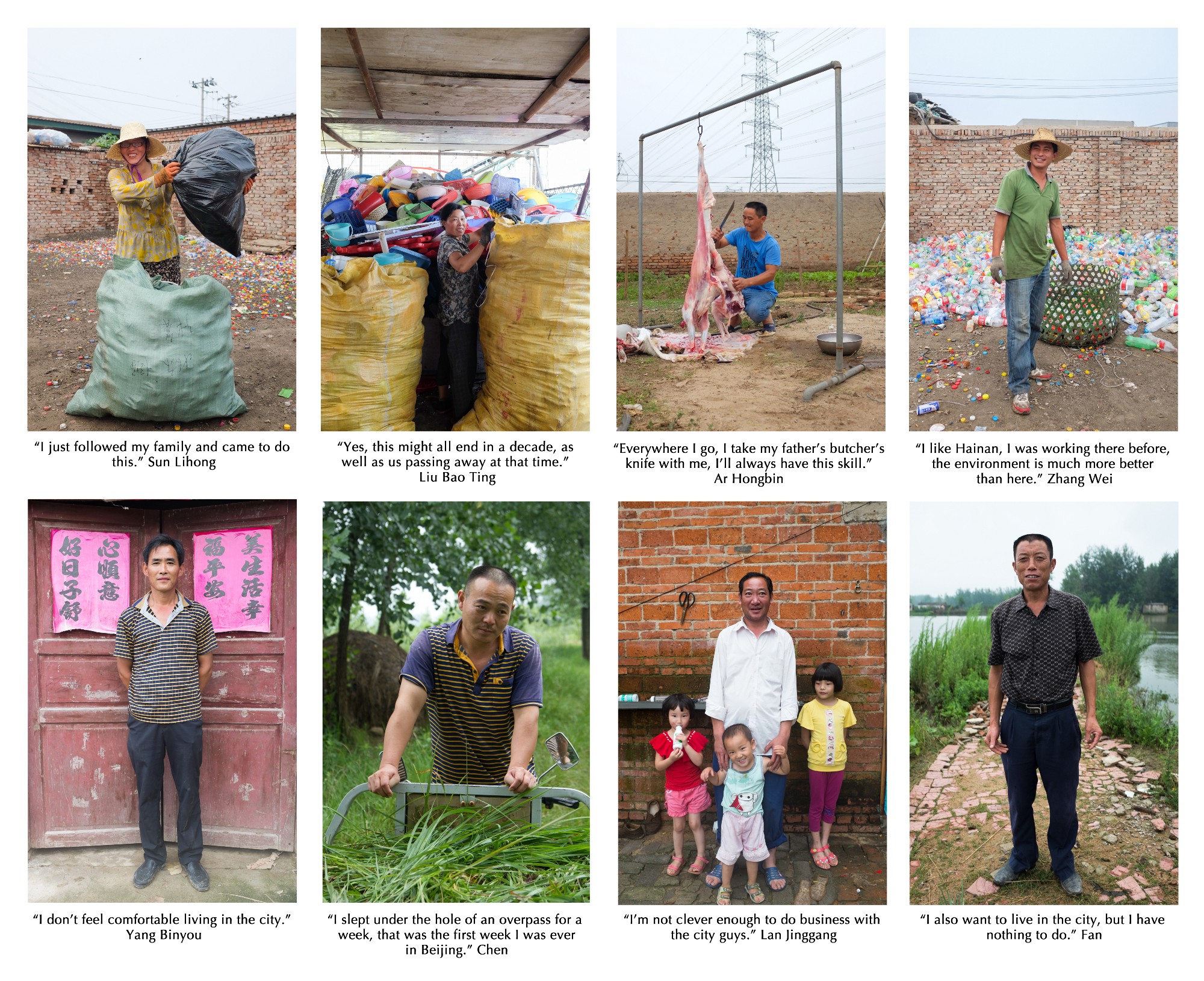

The people of recycling — from Beijing to Gushi, Henan.

““I want to go home because my parents and children are there, so are my relatives and friends.””

Little is known about returning migrants, the left-overs from the great Chinese decades of growth. Faced with a declining industry and lifestyle of sifting through waste, going back home is a serious option. “I want to go home because my parents and children are there, so are my relatives and friends,” says Ah Hongbin. Home has less insecurity around the rising living costs in Beijing, the economic instability, and the uncertainty of whether or not their home and business will be demolished.

Ah Hongbin gave up his recycling business at the start of the year. He works small recycling jobs and is considering returning home to farm.

BACK HOME

In 2013, the fiscal revenue by the Gushi government was 0.77 billion RMB, but its fiscal expenditure totalled 4.72 billion RMB, the gap being subsidised by the central government.

Home for 90% of the recycling workers in Beijing is Gushi, a small county in the southeast of Henan, China. Gushi is the most populous county in Henan, the province with the third largest population in China (~90million). It is also one of the poorest counties in China, enlisted to receive aid and subsidies from the central government.

In the past two years there has been a decline in the amount of rural migrants from Henan across the whole of China. Many now prefer to look for work in the larger towns of their province, rather than the eastern cities that once drew migrants.

Gushi contributes significantly to Henan’s agricultural industry. Agriculture is mainly based on rice, shrimp, turtles and fish (finless eel). Mr Yang, the village representative of Xiong Ji in Gushi, estimates that “90% of the villagers once worked in recycling and 30% of them are now farmers.”

So why return to farm? Agriculture in China is not without challenges. Finding enough land to make a profit is difficult as each individual farmer is allotted land the size of a tennis court (1.5mu). Mass migration to the cities in the last few decades has thinned out the population of farmers in Gushi, and led to more available farmland for the remaining or returning farmers. In 2002, the previous government of President Hu Jintao initiated a financial support system to farmers and insured a more flexible approach to land rights. For example, although the state owns the land in China, it freed up the farmers working it to either rent or exchange their plots between family and friends. “My friend farms my land back home,” says Mr Xiang, a migrant from Gushi who owns a recycling business in Dongxiaokou, Beijing. According to a number of farmers in Gushi, renting land costs somewhere between a bag of rice to 700RMB each year. This is dependent upon the quality of land. In Mr Xiang’s case, he makes no profit from his land.

“I invested 200,000 RMB in fish farming. I borrowed the money from friends and the bank, ” says Mr Lan, a fish farmer who returned to Gushi in 2012. Without property rights, applying for further finance by mortgaging the land to fund a larger more efficient farm is difficult. “Traditional farming (rice and grain) doesn’t make any money, you need to invest in technology to get profit from your land.” Mr Lan farms 30mu (~3 football fields) of land and manages to make a net profit of 60,000RMB each year, money he has recently used to buy two more fish pools.

““If their parents are still working in recycling, their children use recycling as a back up plan, so they just do recycling to wait for another opportunity” ”

Mrs Yang, the wife of a fish farmer, walks home with hay for her small herd of goats.

Living conditions have improved in rural areas since the turn of the century. Government initiatives in healthcare, education and insurance are slowly being implemented across rural China. Although there is a lot of scepticism about the effectiveness and speed of these initiatives, the situation has certainly improved since the 1990s. The thought of being a farmer is a struggle for many people. “I hope the next generation doesn’t stay in the rural areas. I have been to the city, there’s a huge gap between urban and rural. I hope my children can enjoy a better environment,” says Mr Lan.

While the generation raised as farmers in recycling begin their journey back to the farm, the next generation has already started another cycle. They hope for a better job. But what is the reality? “If their parents are still working in recycling, their children use recycling as a back up plan, so they just do recycling to wait for another opportunity,” says Jia Feng, a researcher on Gushi recycling workers in Beijing. Only 6% of rural migrants under the age of 30 have any agricultural training. Life with a job in the city is their future, whether in recycling or not.

“The younger generation want to stay in the city even if they can only earn 2,000RMB a month,” says Yang Bingyou. For the children of Yang Binyou, the situation echoes — his son works with him on the farm while his daughter is in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan. His daughter works in recycling.

by Christine Schindler and Will Wu (thesis project for MA in International Multimedia Journalism, University of Bolton, UK)